Welcome to the eighth edition of the This is the North podcast newsletter.

We’re All Just Not Yet Disabled…

By Alison Dunn, with insights from Calum Grevers.

Calum Grevers

… But we spend remarkable energy avoiding this truth about aging and vulnerability.

Yet as we age, as we become more attuned to the realities 1.3 billion people like Calum Grevers experience daily, we discover inaccessibility everywhere—in our buildings, our apps, and especially in our stories.

This reality hit home when Calum went quiet after I asked him about representation.

"Honestly, I don't think I can think of any.”

I'd just asked if he could remember seeing someone like him portrayed authentically on television. For a moment, this articulate disability campaigner - someone who'd built a successful advocacy career, crowdfunded his own accessible flat, and regularly challenges how society views disability - struggled for words.

When he finally spoke, the only examples were bitter, villainous characters whose disability made them twisted and vengeful. Ivar the Boneless in Vikings. Dr. Strangelove. Disability framed as a source of bitterness or monstrosity, but never as equals.

“I don’t know how you do it”

Actor Peter Sellers as ‘Dr. Strangelove’. Photo from Britannica.

Cruelty isn't always obvious, sometimes it comes wrapped in what people think is empathy.

"I don't know how you do it," people tell Calum. "I'd commit suicide if I were in your position."

The person who said this was actually a support worker - someone employed to care for him. Think about that for a moment. The person paid to help him navigate daily life essentially told him his existence was worse than death.

"What they're really saying is my life is superior to yours," Calum explained. "And yours isn't as good as mine."

Maybe if disabled people weren't invisible on TV, portrayed only as monsters or objects of pity, a support worker wouldn't feel comfortable saying such horrific things. Perhaps if we saw authentic representation - people in love, building careers, and contributing fully to their communities - the thousands of people stranded on waiting lists for accessible housing in Edinburgh would seem as outrageous as it actually is.

This absence of accountability and representation creates a culture where such cruelty feels acceptable. Nowhere is this more evident than online.

Behind anonymous screens, people said things they'd never dare say face-to-face. Calum's experiences revealed something ugly about human nature when accountability disappears.

"Do you want to race because I see the wheels," one 32-year-old marketing manager messaged him. Another compared him to Stephen Hawking. Someone called him a “dead fish," suggesting he was like a dead person.

These weren't teenagers. These were professionals in their twenties and thirties—people supposedly looking for love just like Calum.

But perhaps most telling was the pattern of curiosity exploitation. People would match with him, ask invasive questions about his disability to satisfy their curiosity, then disappear once they'd gotten their answers. He wasn't a potential partner; he was entertainment.

"I realised there's no point using this," he told me. People were comfortable chatting online, but when he suggested meeting in real life, they vanished. He could exist as a digital curiosity, but not as a whole person.

Even the media organisations that claim to champion inclusivity perpetuate this pattern.

The mirror we avoid

Photo by Pexels.

Too scared for truth

Calum has had several offers from big media organisations to cover his story. BBC, major outlets - all expressing interest in his experiences with dating and disability.

But they all fell through. They saw it as "too controversial."

Too controversial? What's controversial about showing that disabled people want love and relationships just like everyone else?

Here's what I keep coming back to: why are we more comfortable with disabled villains than disabled lovers? Why can we watch Ivar the Boneless use his bitterness to become a monster, but we can't handle seeing disabled people as desirable, sexual beings?

The answer lies in our desperate need to believe the world is just.

When we see a disabled villain, we're witnessing what psychologists call "just-world bias" - our brain's attempt to make sense of suffering by deciding it must be deserved. Dr. Strangelove's twisted body reflects his twisted mind. Ivar's physical limitations justify his moral ones.

This serves a crucial function: it protects us from the terrifying randomness of disability. If disabled people are somehow morally different from us - bitter, vengeful, twisted - then we can maintain the illusion that disability won't happen to us good, normal people.

But show us a disabled person in love, living an ordinary life, wanting ordinary things? That shatters our protective delusion. It forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that disability is simply part of human experience - not punishment, not character flaw, just life. And if it's just life, then it could be our life too.

That's what makes authentic disability representation so "controversial." It's not the content that threatens us - it's the mirror.

"I think they just don't think disabled people have sex, or they don't think people want to talk about it," Calum said. "But I think their ideas of what their audience think are not true."

He's right. When disability is represented authentically - remember those groundbreaking Maltesers campaigns that became the brand's most successful in 18 years - audiences respond powerfully. The media's cowardice isn't protecting anyone; it's perpetuating the very ignorance that makes dating apps a nightmare for disabled people.

When I asked Calum about the impact of never seeing positive representation, his answer was stark: "It affects every aspect of their lives. They're not seen as important. They're not seen as participants in society."

We're talking about 20% of the global population—over a billion people worldwide. Yet we treat them as a niche group, as "other," as people whose full humanity we can ignore.

But disability doesn't discriminate. You can become disabled at any point in your life. Most of us will, eventually. When you're in your seventies, eighties or nineties, you'll want the world to be as inclusive and accessible as possible.

We think we're avoiding uncomfortable truths by keeping disability invisible, but we're just postponing our own reckoning with reality.

Photo from Getty Images.

Hope in the face of cruelty

Photo from Maltesers campaign by Mars Inc.

Despite years of rejection and casual cruelty, Calum approaches even hostile encounters with compassion. Drawing inspiration from Martin Luther King Jr., he believes people's negative attitudes are products of an environment that's failed to show positive disability representation.

"Be compassionate to people with negative attitudes," he told me. "How else are you going to change their view?"

Writing about these deeply personal experiences is "quite traumatising," he admits. Yet he continues because someone has to force these uncomfortable conversations.

His advice for those wanting to become better allies is refreshingly simple: "Just say hello. That's the start."

The fear of saying something wrong often prevents any interaction at all. But Calum wants the same things most people do—he just might need different support to achieve them. The misconceptions that make dating apps hellish and media organisations cowardly aren't protecting anyone. They're limiting everyone.

Calum may not be able to think of positive disabled characters on TV, but everyone who heard his story—everyone who donated to his housing campaign, everyone who follows his journey - now knows one. Sometimes representation starts with refusing to be invisible.

The next time you see a disabled character on screen - or notice their absence - you'll think of Calum. You'll recognise the psychological game we're all playing, the mirrors we're all avoiding. And maybe you'll understand why refusing to look away isn't just good for disabled people. It's practice for the person you'll inevitably become.

Until next time,

Alison.

Listen to the full This is the North podcast:

> Spotify

> Apple Podcasts

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please like, share and subscribe. It takes less than 10 seconds and makes you part of something essential: a community of people who believe transformative conversations can become catalysts for positive change.

This Is The North is your source for transformative conversations that challenge systems holding back the North of England. Hosted by Alison Dunn, supported by Society Matters Foundation.

A deep dive into the archive…

I’m not actually diving too deeply this month, only going back to episode 29 entitled Beyond the Medicine Cabinet : Re-imagining health. In this conversation I spoke with Dr Brigid Joughin, a GP and former trustee of Ways to Wellness and Steffen Laukard, the Lead for the Persistent Pain project at Ways for Wellness.

This conversation examines Ways to Wellness’ innovating approach to health that addresses the “wider determinants of health” – housing, social connection and joy – many of the things that Calum Grevers talked about in our recent recording of episode 33. These factors often have a greater impact on health than medicine alone. Through social prescribing, this groundbreaking organisation is demonstrating that listening, acknowledging grief, and creating space for joy can transform lives while potentially reducing pressure of the NHS.

This week I have been listening to…

A very different subject for me, but I happened to catch Witness History, Discovering the Titanic on my drive home and two things hit me like a truck. Firstly, it is 40 years since the location of the Titanic was first discovered – 1985. I find it really hard to believe four decades have gone by, it feels like only yesterday I was sat in front of my television – a television with only four or five channels – watching the first pictures emerge of this mythical ship.

The other thing to say about this podcast is the incredibly powerful audio of survivors from the sinking sharing their testimony of what happened that fateful night. The producers of this episode of Witness History have done such a good job of cleaning up the audio it really does sound as if the survivors are in the studio this very day calmly sharing stories of what must have been a life changing trauma. It’s only ten minutes long and well worth a listen BBC World Service - Witness History, Discovering the Titanic

This week I have been reading…

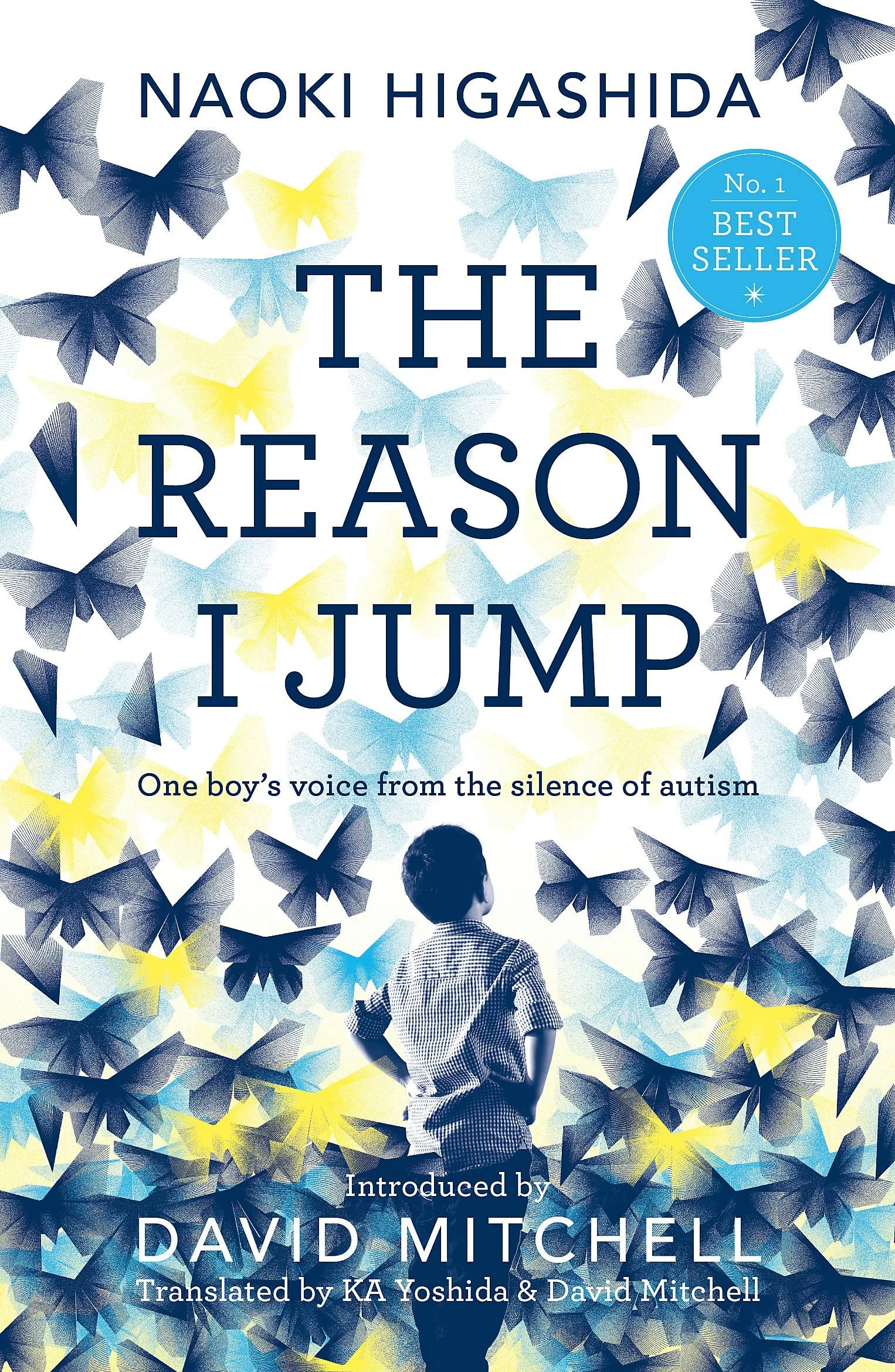

The reason I jump – one boy’s story from the silence of autism. Naoki Higashida's memoir that offers a unique perspective on life as a child with autism, something I am incredibly interested in as the grandmother of an autistic boy. I often wonder how my grandson sees the world land I think this book is the closest I will ever come to understanding that. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Written by Naoki when he was thirteen, the book uses a question-and-answer format to reveal his thoughts, feelings, and perceptions of the world. Naoki explains behaviors that may seem baffling, such as why he likes to jump, why some people with autism dislike being touched and why some children with autism may hurt themselves or others a very real challenge in our house. He also shares his thoughts on time, life, beauty, and nature, and even includes a short story which I found really uplifting.

This is a book I feel that everyone should read, and if you pick it up I’d love to know what you think about it.

This week I visited…

A great friend of This is the North, Professor Greta Defeyter at Northumbria University, along with Gateshead Council, Northumberland Council and Newcastle City Council, to celebrate the Department for Education Holiday Activity and Food (HAF) Programme and all that is great about the young people in our region.

The HAF programme gives children and young people who receive free school meals the chance to enjoy healthy food and take part in fun, active and creative sessions during the school holidays. It’s been shown to help with everything from wellbeing and friendships to easing pressure on families - and now, thanks to research led by Professor Defeyter, it’s secured a £600 million boost from the government, as reported in The Independent.

With that good news and a suite of activities to follow, what a day we had! Everything from dodgeball to LEGO games, from a climbing wall to baking flapjacks - you name it and Northumbria delivered it. The young people had a thoroughly enjoyable day, with great food, lots of new friends, and some fantastic stories to tell when they return to school.